Table of Contents

For a certain generation, the name Tamiya doesn’t just represent a brand; it evokes a multi-sensory memory, a sacred childhood ritual. It began with the box. Long before you ever touched a single piece of plastic, you were captivated by the artwork—a dynamic, impossibly cool painting of a tank cresting a hill, a race car blurring past the finish line, or a buggy kicking up a rooster tail of dirt.1 These weren’t just illustrations; they were promises of adventure, masterpieces by artists like Shigeru Komatsuzaki that fired the imagination and justified weeks of saved-up allowance.

Then came the crinkle of the cellophane wrap, a sound pregnant with possibility. Peeling it back released the brand’s signature perfume: the clean, slightly sweet, and utterly distinct smell of high-quality polystyrene plastic. Inside, the contents were laid out with an almost surgical precision. Parts weren’t just tossed in a bag; they were presented on frames called “sprues,” each component perfectly formed, numbered, and waiting to be liberated.3 This was your first clue that you weren’t just playing with a toy. You were engaging in an act of creation.

The process was a rite of passage. It was a lesson in following instructions, a test of a child’s nascent ability to delay gratification. It was a battle of wits against microscopic screws that seemed to possess a quantum ability to vanish the moment they touched a carpet. It was the discovery of Tamiya cement, a substance that formed an eternal covenant between two pieces of plastic, or, more often, between your own fingertips.3 And it was the quiet anxiety of applying the decals, holding your breath as you slid the delicate film into place, knowing that one sneeze could turn your pristine Porsche into a modern art disaster.

But the reward for this crucible of patience was a profound sense of accomplishment. You hadn’t just bought a toy; you had built it. You had transformed a collection of inert plastic parts into something tangible, something real. This experience—this journey from box art to finished model—is the foundation of the Tamiya legacy. It’s the story of a company that didn’t just sell products, but sold the very experience of craftsmanship to millions of kids around the world. And like any great story, it starts with a lot of wood, a catastrophic fire, and a tank that accidentally changed everything.

Chapter 1: From Splinters to Sprues: The Unlikely Birth of a Hobby Giant

Tamiya’s path to becoming a global hobby icon was not a carefully planned march to victory. It was a chaotic stumble through market shifts, catastrophic failures, and fortunate accidents that, through a combination of stubborn perseverance and brilliant pragmatism, always managed to land them on their feet. The company’s origin story is less a corporate blueprint and more a comedy of errors that somehow resulted in genius.

The Founder’s Hustle

The story begins not with a toymaker, but with a restless entrepreneur named Yoshio Tamiya (1905-1988). Born into a family in the tea industry, Yoshio had little interest in staying put. His early career was a whirlwind of ventures that reads like a random job generator: by nineteen, he was working in an auto repair shop, and by thirty, he was running his own transportation company, complete with trucks, vans, and even a bus service.5 He was a man of engines and industry, not models and miniatures.

Like many Japanese industrialists, his business was utterly obliterated by Allied air raids in 1945. In a twist of fate that would prove crucial for hobbyists everywhere, Yoshio had avoided being drafted into the war due to a foot injury.6 This personal misfortune was the world’s good luck, as it allowed him to survive and start over. Rising from the ashes, he founded Tamiya Shoji & Co. in 1946 in Shizuoka, a city that would one day be known as the “Model Capital” of Japan. His new business? A humble sawmill and lumber company.2

The Wooden Age (and its Fiery End)

With a surplus of wood and a market in need of educational toys, the pivot to making wooden model kits in 1947 was a logical one.6 Tamiya began producing high-quality scale models of ships and airplanes, quickly earning a reputation for craftsmanship. For a few years, the business hummed along, a quiet marriage of lumber and hobby.

Then, in 1951, the universe decided to give Tamiya a rather forceful push in the right direction. A fire broke out and burned the factory to the ground.5 For most, this would have been the end. For Yoshio Tamiya, it was a moment of brutal clarity. Instead of rebuilding the lumber business, he made a fateful decision in 1953: he would abandon wood processing entirely and focus 100% on model making.7 The fire hadn’t destroyed his company; it had forged its new identity.

The Plastic Problem Child: The Battleship Yamato

The mid-1950s brought a new threat, one that couldn’t be extinguished with water. Cheap, detailed plastic models began pouring in from overseas, and the market for wooden kits began to dry up.2 Tamiya, ever the pragmatist, decided to join the plastic revolution. In 1960, they launched their first-ever plastic model kit: a 1/800 scale replica of the Japanese battleship Yamato.2

It was a complete and utter disaster.

The problem was economic. Tamiya’s competitors were already selling similar kits for a mere 350 yen. To compete, Tamiya had to match the price. However, the complex, curved shapes of the battleship required incredibly intricate and expensive metal molds to produce. At 350 yen a pop, Tamiya was losing money on every single box they sold. They couldn’t possibly recoup the astronomical cost of the molds.2 Bruised and financially battered, the company was forced to retreat, temporarily refocusing on their familiar wooden models. Their first foray into the future of modeling had been a costly failure.

Salvation by Panther: The Accidental Standard-Bearer

The lesson learned from the Yamato‘s failure was brutal but simple: complex shapes are expensive. So, when Tamiya decided to try their hand at plastic again in 1961, they chose their subject with pure, unadulterated pragmatism. They didn’t pick a famous hero tank or a sleek, beautiful vehicle. They picked the German Panther tank for one reason and one reason only: it was boxy. Its “linear form,” as the company history politely puts it, would make the molds dramatically simpler and cheaper to produce.2

This time, everything clicked. The motorized Panther tank was a runaway hit.2 It wasn’t just the smart production choice that made it successful; the kit itself was a masterpiece of user-friendly design. It was motorized and performed well, the instructions were clear and easy for a child to follow, and the box art was a stunning piece of visual storytelling.2

But the kit’s most enduring legacy was a complete accident. The designers needed the tank to hold a motor and batteries. They decided to make the hull just large enough to fit two Type 2 batteries, even though the motor only required one for its function.2 The resulting scale of the model worked out to be 1:35. It was a number chosen not by market research or strategic planning, but by the physical dimensions of a battery compartment. In one of history’s greatest hobby-related flukes, this arbitrary 1:35 scale became the undisputed global standard for military modeling, a standard that persists to this day.2 Had they used a different battery, generations of modelers might be building in 1:40 scale.

The success of the Panther was transformative. It provided the financial foundation for Tamiya to establish its own in-house mold-making division in 1964, giving them unparalleled control over the quality and precision of their products.2 This vertical integration was the key to fulfilling their new motto, a promise that would define the brand for decades to come: “First in Quality Around the World”.9

Chapter 2: The RC Revolution: When the Backyard Became Baja

Having mastered the world of static models, Tamiya turned its obsessive attention to a new frontier in the 1970s: radio-controlled vehicles. They didn’t just enter the market; they redefined it. By applying their static model philosophy of extreme realism and mechanical intrigue to cars that could actually move, Tamiya created a global phenomenon that turned countless backyards and parking lots into miniature race tracks.

The Spark: Porsche, Precision, and Power

Tamiya’s grand entrance into the RC world came in 1976 with a 1/12 scale model of the Porsche 934 Turbo RSR.9 This was no mere toy. It was a high-performance, stunningly detailed kit that is widely credited with igniting the RC car boom.8 This release signaled that Tamiya was bringing its “First in Quality” ethos to a whole new dimension.

Under the leadership of Yoshio’s son, Shunsaku Tamiya, the company’s dedication to accuracy became the stuff of legend. Shunsaku wasn’t content with just looking at photographs. He would personally visit military museums, and when photos weren’t allowed, he and his team would frantically sketch what they saw from memory after the visit.1 This fanaticism reached its peak in the 1970s when, to research an upcoming model, Tamiya simply went out and bought a real Porsche 911 so they could take it apart piece by piece. They then had to sheepishly ask a dealer for help putting it back together.1 This wasn’t just business; it was a borderline-obsessive quest for perfection.

The Legend: The Sand Scorcher (1979) – The Unattainable Dream

If the Porsche was the spark, the Sand Scorcher was the inferno. Released on December 15, 1979, this 1/10 scale replica of a Volkswagen Baja Bug was, for many kids, the ultimate object of desire—the holy grail of RC cars.13 It was expensive, complex, and so impossibly cool that its box art alone could sustain a child’s daydreams for months.

What made the Sand Scorcher a legend was that it blurred the line between a model and a genuine piece of off-road machinery. This was achieved through several key features that prioritized realism over everything else:

- Metal Construction: Unlike its plastic contemporaries, the Sand Scorcher was built like a tank. Its chassis, suspension arms, and other key components were made of cast aluminum and metal, making it heavy but incredibly rugged.13

- Realistic Suspension: The suspension system wasn’t just functional; it was a near-perfect scale replica of the trailing arm and swing axle suspension found on a real-life VW Beetle. This commitment to mechanical accuracy was unheard of.14

- Advanced Shocks: It featured oil-filled shock absorbers, a first for its time, which gave it a far more realistic and controlled ride than the simple spring suspensions of lesser toys.15

- Water-Resistant Electronics: The delicate radio gear and battery were housed in a clear, water-resistant plastic case, meaning you could actually drive it through puddles without fear of a catastrophic electrical meltdown.14

The Sand Scorcher was more than a toy; it was an engineering statement. It demonstrated that Tamiya’s core identity, inherited from their static model business, was about celebrating the beauty of mechanical design. It wasn’t necessarily the fastest or best-handling car for competitive racing, but it was arguably the most authentic and satisfying to build and own.

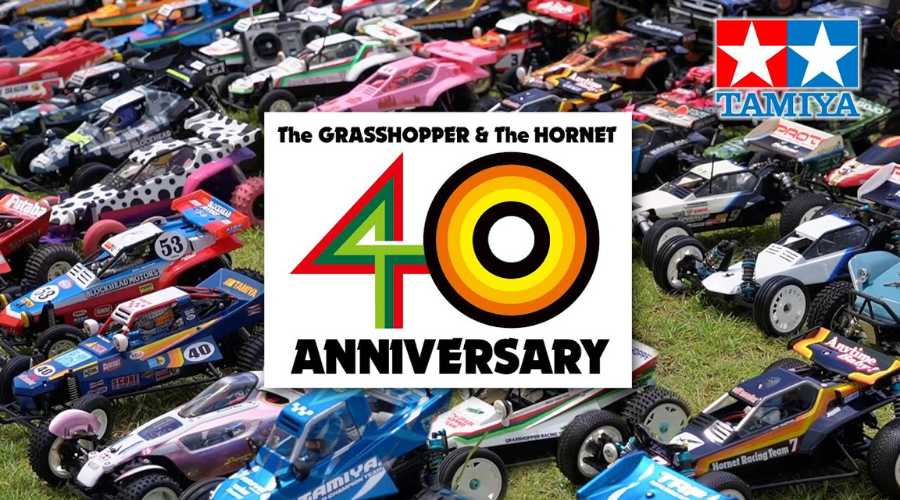

The People’s Champion: The Grasshopper (1984) – The Gateway Drug

While the Sand Scorcher was the aspirational dream, the Tamiya Grasshopper was the attainable reality that brought the hobby to the masses. Released in May 1984, this simple, tough, and affordable buggy became the quintessential entry point into the world of “real” RC cars for an entire generation.16

Where the Sand Scorcher was complex and metallic, the Grasshopper was a masterpiece of elegant simplicity. Its appeal lay in a perfect storm of accessibility and brilliant design:

- Ease of Assembly: The kit was designed to be easy to build, with a rugged plastic “bathtub” monocoque chassis that could absorb a tremendous amount of abuse from inexperienced drivers.16

- Beginner-Friendly Performance: It was equipped with a modest Mabuchi 380-size motor. This made it slower and more manageable than its more powerful, 540-motor-equipped siblings like The Hornet, giving new drivers a chance to learn without instantly crashing their prized possession into a curb at 20 mph.16

- Iconic Design: The car was based on real-life single-seater Baja buggies, but its aesthetic was pure 80s genius. With its angular white body, bright green decals, and a profile that subtly mimicked the insect it was named after, the Grasshopper was instantly recognizable and memorable.16

The Grasshopper perfectly illustrates Tamiya’s brilliant market strategy. They created a two-tiered system: the high-end, complex models like the Sand Scorcher built brand prestige and catered to serious enthusiasts, while affordable, user-friendly kits like the Grasshopper created a massive, loyal customer base. A kid could start with a Grasshopper, get hooked on the hobby, and then spend years aspiring to own the more advanced models in the Tamiya catalog. It was a perfect system for creating lifelong fans.

The Hall of Fame: A Quick-Fire Tribute

Of course, the Grasshopper wasn’t alone. The 80s were a golden age for Tamiya RC, producing a stable of legendary vehicles that are still revered today. No history would be complete without a nod to:

- The Hornet: The Grasshopper’s faster, angrier older brother. It shared a similar chassis but packed a 540 motor, making it the go-to choice for kids with a need for speed.9

- The Frog: A revolutionary buggy with a space-frame chassis and independent rear suspension, it was a more advanced and capable racer that became an icon in its own right.9

- The Lunch Box: The glorious, bright yellow van that spent more time on its two rear wheels than all four. Its tendency to perform uncontrollable wheelies on command made it one of the most entertaining RC vehicles ever created.21

- The Clod Buster: The undisputed king of the monster trucks. With its massive tires, dual motors, and four-wheel steering, this beast was the backyard monster truck champion of the world.22

These machines, and many others, cemented Tamiya’s dominance. They weren’t just selling RC cars; they were selling distinct personalities, each with its own quirks and charms, that became cherished companions in childhood adventures.

Chapter 3: The Mini 4WD Phenomenon: How Two AA Batteries Conquered the World

If static models built Tamiya’s reputation for quality and RC cars made them a household name, then Mini 4WD transformed them into a global cultural force. This line of tiny, non-radio-controlled, battery-powered cars became more than just a product; it was a phenomenon, a subculture complete with its own heroes, lore, and a deeply engaging ecosystem of customization that served as a generation’s first introduction to the principles of engineering.

The Birth of a Legend (1982)

The Mini 4WD story began in 1982 with the release of realistic models like the Ford Ranger 4×4 and Chevrolet Pickup.23 The concept was simple but brilliant: a 1:32 scale, snap-together model car powered by a small electric motor and two AA batteries, designed to race on a special U-shaped track.23

This new line was perfectly positioned. For kids who dreamed of owning a Tamiya RC buggy but couldn’t afford the high price tag, the Mini 4WD was the perfect alternative. It offered the same hands-on building experience and the thrill of motorized action at a fraction of the cost.25 It was, in essence, a “running plastic model,” and it was about to take over the world.

The First Boom (Late 80s-Early 90s): Dash! Yonkuro

The hobby bubbled along for several years until 1987, when a manga series titled Dash! Yonkuro appeared in the popular CoroCoro Comic magazine.25 The subsequent anime adaptation, which began airing in 1989, was the spark that ignited the first Mini 4WD inferno.28

The series followed the adventures of Yonkuro Hinomaru and his racing team, the “Dash Warriors.” They weren’t just racing cars; they were battling rivals with legendary machines like the Dash-1 Emperor, Dash-2 Burning Sun, and Dash-3 Shooting Star.30 The anime gave the hobby a narrative, a cast of heroes, and a set of iconic cars that kids were desperate to own and race themselves.

This media blitz was a stroke of marketing genius. It created an immense demand that Tamiya was more than happy to supply. The boom also led to the establishment of the first official Tamiya Japan Cup in 1988, a nationwide tournament that legitimized the hobby and gave young racers a competitive stage to showcase their creations.25 By 1990, Tamiya had sold over 50 million Mini 4WD units, a testament to the power of a good story and a great toy.25

The Second Boom (Mid-to-Late 90s): Bakusō Kyōdai Let’s & Go!!

Just as the first boom began to fade, Tamiya and Shogakukan teamed up again, launching a new manga in 1994 that would trigger a second, even more massive global explosion of popularity: Bakusō Kyōdai Let’s & Go!!.25

This series centered on the rivalry between two brothers, Retsu and Go Seiba. Each had a distinct racing philosophy, reflected in their iconic cars. Retsu, the more strategic and technical racer, piloted the well-rounded Sonic series of cars (like the Sonic Saber and Vanguard Sonic), known for their balance and cornering ability. Go, the hot-headed speed demon, drove the aggressive Magnum series (like the Magnum Saber and Victory Magnum), which were all about raw, straight-line velocity.34

The Let’s & Go!! anime, which ran from 1996 to 1998, was a worldwide hit, particularly throughout Asia, including countries like Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Malaysia.33 Hobby shops with elaborate tracks popped up everywhere. Schoolyards buzzed with talk of the latest episode and the newest car release. The series introduced the sleek “Fully Cowled” Mini 4WD designs, and by 1997, Tamiya’s cumulative sales had skyrocketed past an astonishing 100 million units.25 This wasn’t just a hobby anymore; it was a full-blown cultural phenomenon.

The Art of the Tune-Up: A Kid’s First Engineering Degree

The true, enduring genius of Mini 4WD wasn’t just the cars themselves, but the rich and complex ecosystem of customization that grew around them. A stock car out of the box was just the beginning. The real magic lay in the endless array of “Grade-Up Parts” that allowed a racer to tune, tweak, and transform their machine into a high-performance beast.24

This process was, for millions of kids, an accidental but incredibly effective introduction to the fundamental concepts of science and engineering. Without realizing it, they were conducting hands-on experiments in physics. They learned about the trade-off between torque and speed by swapping out gear ratios.24 They explored friction and efficiency by replacing standard plastic bushings with smooth ball bearings.24 They grappled with concepts of momentum and center of gravity by strategically placing “mass dampers” to keep their cars from flying off the track after a jump.41 It was a STEM education program disguised as playtime, as Shunsaku Tamiya himself noted was a goal: to foster future engineers.44

The culture of tuning was a world unto itself, filled with its own language, legends, and hotly debated theories whispered in hobby shop aisles.

Table 1: The Mini 4WD Tuner’s Toolkit: A Guide to Going Faster (or Flying Off the Track with Style)

| Part Type | Popular Examples | What It Actually Does (In Kid Language) |

| Motors | Torque-Tuned, Atomic-Tuned, Hyper-Dash, Plasma-Dash 42 | The Soul of the Machine. This was the heart of your car. You started with the stock motor, but soon you were begging your parents for a Hyper-Dash. This was the motor your friend swore was illegal because it was “too fast.” It was the difference between a respectable finish and launching your car into low-earth orbit on the first jump. |

| Rollers | 13mm/19mm Aluminum Ball-Race Rollers, Plastic Rollers, Double Rollers 42 | The Guard Rails. These little wheels were the only thing keeping your car from grinding to a halt on a corner. Upgrading from the stock plastic ones to a set of shiny aluminum ball-bearing rollers was a major status symbol and the first sign you were getting serious. Double rollers were for pros who were tired of their car flipping over on the banked curve. |

| Tires & Wheels | Sponge Tires, Hard/Low-Profile Tires, Large/Small Diameter Wheels, One-Way Wheels 24 | The Shoes. The great debate of the 90s. Sponge tires had insane grip but would pick up every speck of dust on the track and become useless in five seconds. Hard, low-profile tires were for speed demons. And everyone had a theory: small wheels for better acceleration out of corners, or big wheels for higher top speed on the straights? |

| Gears | High-Speed Gear Sets (e.g., $3.5:1$, $4:1$, $5:1$) 24 | The Transmission. The most confusing part for any 10-year-old. You just knew the blue and orange one ($4:1$) was for technical, twisty tracks and the green and light-green one ($3.5:1$) was for long, high-speed layouts. Getting this wrong meant your car would be embarrassingly slow, no matter how cool your motor was. |

| Mass Dampers | Bullet Type, Barrel Type, Side Dampers 41 | The Bouncy Castles. Those little metal weights that bobbed up and down on screws. Their job was to absorb the shock of a landing and stop your car from bouncing into another dimension after a jump. The more of these you had hanging off your car, the more “pro” your setup looked. |

| Chassis | Super-1, Super-II, VS, MA, FM-A 39 | The Skeleton. The frame that held everything together. You probably started with whatever came in the box, but true masters knew the secrets of each chassis: the lightweight and agile VS, the stable and modern MA, or the unique front-motor FM-A that excelled on hilly courses. |

This entire system was a masterclass in creating a self-perpetuating hobby ecosystem. The anime created the desire for the cars. The affordable base kits fulfilled that initial desire. The vast array of upgrade parts deepened the user’s engagement and investment. Finally, the official races and local hobby shop tracks provided a community and a platform for validation, which in turn fueled more interest in the anime and products. It was a perfect, closed-loop system that turned a simple toy into a lifelong passion.

Chapter 4: The Tamiya Legacy: More Than Just Toys

The twin stars on the Tamiya logo represent passion and precision, but over the decades, they have come to symbolize something more: endurance.1 While other childhood fads have come and gone, Tamiya has remained a constant, a benchmark for quality and a cornerstone of the hobby world. Its legacy is not just in the millions of kits sold, but in the skills, memories, and communities it has built.

The Third Boom: Nostalgia is a High-Speed Motor

Around 2012, something remarkable began to happen. The Mini 4WD scene, which had quieted down after the second boom of the late 90s, roared back to life.28 This “third boom” was different. It wasn’t driven by a new anime series, but by a powerful force: nostalgia. The kids who grew up idolizing Yonkuro Hinomaru and the Seiba brothers were now adults with jobs, disposable income, and a deep-seated desire to reconnect with a cherished part of their youth.27

This resurgence was kicked into high gear by the revival of the Japan Cup after a 13-year hiatus.25 Suddenly, fathers were showing up at tracks with their own children, passing the torch to a new generation.28 This new wave of adult racers brought a new level of sophistication to the hobby. Armed with a better understanding of engineering principles (and better tools), they developed advanced building techniques and pushed the limits of what the tiny cars could do. This led to the formalization of new racing classes, like the popular “B-Max” (Basic Max) class, which limits modifications to create a more level playing field, and the “Open Class,” where radical, custom machining is allowed.53 The hobby had evolved from a children’s pastime into a multi-generational community.

“First in Quality” as an Enduring Philosophy

The foundation of Tamiya’s enduring appeal is its unwavering commitment to its founding motto: “First in Quality Around the World”.9 This isn’t just a marketing slogan; it’s a tangible aspect of the user experience. A Tamiya kit is renowned for its precision engineering. The parts fit together perfectly. The molds are clean, with almost no excess plastic “flash” that needs to be trimmed away. The instructions are models of clarity.2

This dedication to quality is why a Tamiya kit designed in the 1980s can be re-released today and still feel like a premium product. It assembles just as perfectly now as it did then, a testament to the masterful craftsmanship of their mold-making.44 This reliability and respect for the builder is what has earned Tamiya its sterling reputation and has kept hobbyists coming back for over half a century.

A Global Community Built on Tiny Cars

What started in a small workshop in Shizuoka has blossomed into a vibrant, global community. Tamiya is not just a Japanese company; it’s an international institution. Major Mini 4WD events like the Asia Challenge bring together top racers from Taiwan, Thailand, South Korea, Indonesia, the Philippines, and beyond.26 Thriving racing scenes have emerged in the United States and Europe, centered around dedicated hobby shops and passionate fan groups.33

The hobby has a unique way of fostering connection. It can be a solitary act of creation at a workbench, but it becomes a social experience at the racetrack. Friendships are forged over shared toolboxes, and rivalries are born on the banked curves of a plastic track. In an increasingly digital world, Tamiya provides a tangible, hands-on way for people to connect, compete, and share a common passion.28

Conclusion: The Unseen Product

To trace the history of Tamiya is to trace a journey from a lumber mill ravaged by war to a global cultural icon. It’s a story of resilience, innovation, and an almost fanatical dedication to quality. From the accidental standardization of military modeling with the 1:35 Panther tank, to the hyper-realistic engineering of the Sand Scorcher, to the world-conquering phenomenon of the Mini 4WD, Tamiya has consistently done more than just manufacture toys.

In the end, Tamiya’s most important and enduring product was never made of plastic. It wasn’t the static model, the RC car, or the Mini 4WD kit. Their true product was the experience itself. It was the patience learned while sanding a tiny seam line to perfection. It was the creativity sparked by a custom paint job or a unique decal placement. It was the critical thinking and problem-solving skills honed by trying to figure out why your car kept flying off the same corner.

Most importantly, it was the millions of childhood memories built, one snap-fit part at a time, in garages, basements, and at hobby shop tracks around the world. Tamiya didn’t just sell us models; they gave us the tools to build a small piece of our own childhoods. And that is a legacy that will last forever.

Leave a Comment